Women’s Rights group pushes for protection of donkeys

A LOCAL women's rights group has called for urgent legal reforms to protect donkeys, which are increasingly becoming vital to the survival and livelihoods of rural women.

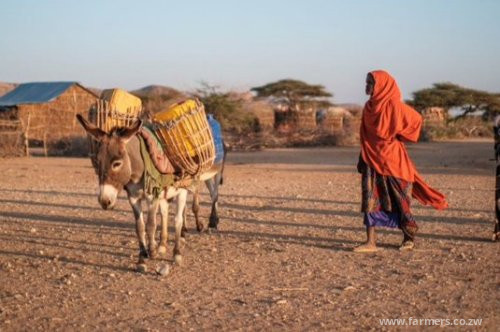

Communities in arid districts such as Beitbridge, Mwenezi, Gwanda and Lupane have turned to donkeys as the last line of defence against worsening droughts, livestock losses and rural poverty.

In many areas, donkeys have become the backbone of rural life, used for tilling the land, fetching water and used as a mode of transport to carry goods and accessing healthcare services, especially for women.

“We are pushing for amendments to this Act [Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act] because it has major loopholes,” Women and Land Zimbabwe (WLZ) project co-ordinator Prince Ndlovu told NewsDay Farming.

“It was last amended over two decades ago and still carries colonial-era language that excluded donkeys from key protections, simply because they were associated with poor black communities and not commercial farming.”

WLZ is a partner organisation of the British-based Womankind Worldwide that supports women’s empowerment.

Its main focus is on rural women to facilitate the eradication of gender discrimination in access, ownership and control of land, natural resources and related opportunities for sustainable livelihoods of socially and economically disadvantaged/excluded women in Zimbabwe.

The existing legislation does not classify donkeys as livestock in Zimbabwe.

Instead, donkeys are covered under environmental laws overseen by the Ministry of Environment, Climate and Wildlife, a legal mismatch that has created gaps in enforcement and left the animals vulnerable to neglect, abuse and theft.

Ndlovu said criminals were taking advantage of these legal gaps to steal donkeys, often mutilating them to erase ownership brands using hot irons or pouring boiling water on their skins.

In some reported cases, thieves have chopped off donkeys’ ears to disguise their identity.

“Because donkeys aren’t defined as livestock, the penalties for cruelty or theft are weak. Offenders often walk free or pay fines as low as US$200,” Ndlovu said.

“The Act doesn’t even specify what constitutes overloading or overworking donkeys, making it hard to enforce protection.”

WLZ is pushing for an overhaul of the legislation to include clear definitions, deterrent penalties and the reclassification of donkeys under agricultural laws.

Ndlovu added that this would allow government departments responsible for livestock health to support donkey welfare programmes in the same way they do for cattle, goats, or sheep.

Beyond animal rights, the issue is deeply tied to gender and economic justice.

In many parts of rural Zimbabwe, donkeys are the only affordable draught animals left standing after successive droughts wiped out cattle herds.

Their role in agriculture, water collection and transportation has made them indispensable to women.

“Donkeys are the backs, shoulders and legs of rural women. They reduce the burden of domestic chores and give women the time to focus on income-generating activities,” Ndlovu said.

He noted that donkeys are more gender-neutral than cattle, meaning women and children can handle them more easily for ploughing, carting goods, or travelling to clinics.

“Donkeys are often used to transport water, firewood, produce from gardens to markets and even ferry sick family members to health centres where there is no ambulance service,” Ndlovu said.

With financial and technical support, WLZ is rolling out a donkey welfare project aimed at improving care for working donkeys and raising awareness in communities.

The project promotes the production of fodder gardens to improve donkey nutrition, particularly in the dry season, and has helped drill solar-powered boreholes in drought-prone areas such as Nkayi, Gwanda and Lupane to provide access to clean drinking water for donkeys.

“We’ve capacitated communities to better care for their donkeys by shifting attitudes and showing the value of these animals. In the past, they were taken for granted. But now, with climate change pushing cattle out, donkeys are stepping in,” Ndlovu said.

As climate pressures increase and rural livelihoods become more fragile, stakeholders say it is critical for policymakers to act.

Ndlovu said recognising donkeys as livestock and integrating them into national agricultural, climate resilience and gender policies would go a long way in improving outcomes for rural women.

“We hope Parliament will support this shift and help us bring donkeys into the mainstream of livestock development. It’s not just about the animals, it's about the women and families who depend on them for survival,” Ndlovu said.

As a result, they are excluded from national livestock development programmes and denied protection under the Animal Health Act, which is administered by the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development.