Chinese Demand for Donkey Skins Depletes Valuable African Animal

Ejiao is considered a miracle elixir for those who use it. However, it has become a disaster for Africa’s donkeys and the communities that rely on them.

The Chinese demand for donkey skins and meat fuels a black market in several African countries. Those markets benefit transnational organized criminal groups, which rely on lax regulations, public corruption and porous borders to traffic in skins.

Gelatin made by boiling donkey skins forms the basis for ejiao (pronounced “eh-gee-yow”), which users take as a treatment for anemia and other blood disorders. The demand for ejiao in China has decimated that nation’s donkey population, which plunged from 11.1 million animals in 1990 to 2.5 million in 2018.

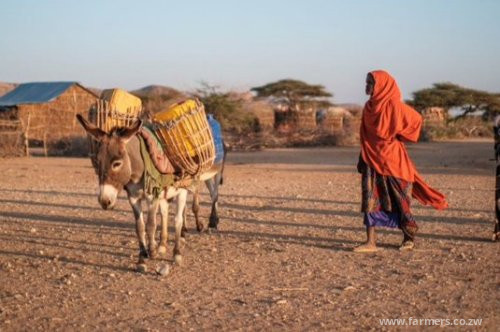

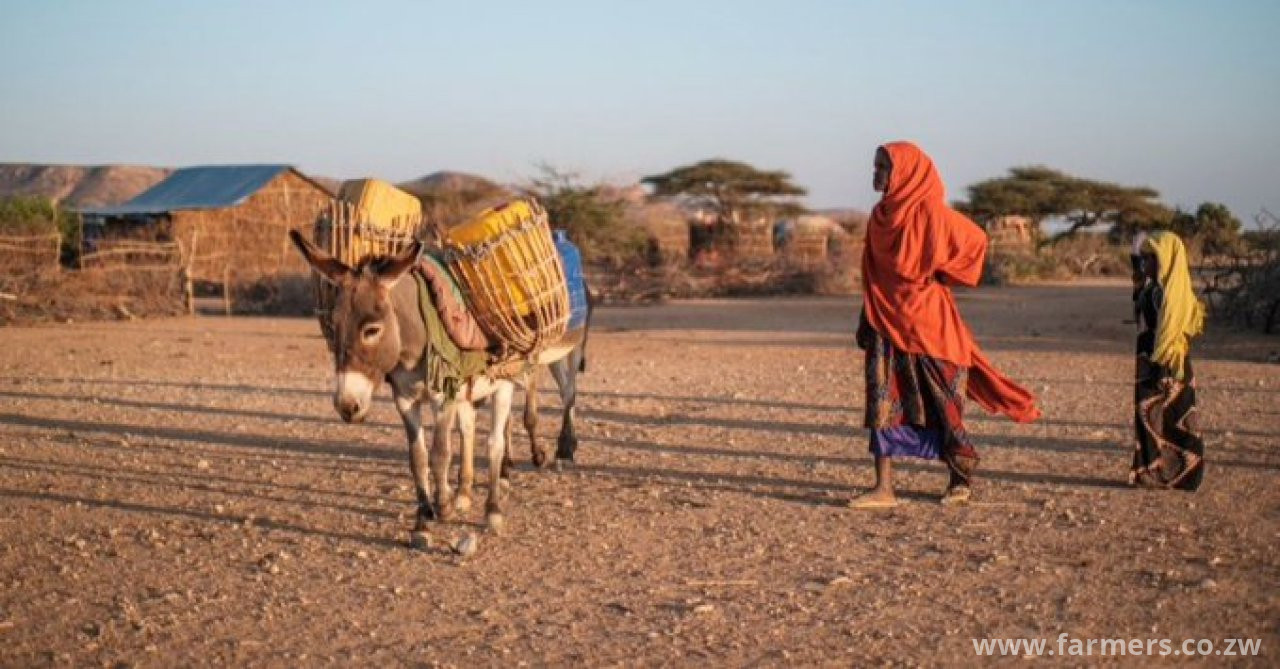

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) makers have, in turn, sought donkey hides in Kenya and elsewhere, where donkeys are crucial to rural communities. Chinese demand fuels widespread theft of donkeys in those communities, stripping some owners of an important part of their livelihood.

Beyond the potential economic damage to rural communities, the trade in donkey skins for TCM also raises the specter of spreading zoonotic diseases, such as glanders, from animals to people, experts say. Glanders is a rare, equine-borne disease that can be fatal to people.

Imported skins account for 90% of ejiao production, according to Brooke Action for Working Horses and Donkeys, an animal welfare organization formed in Egypt in 1934. It is now based in the United Kingdom.

Writing for Global China Pulse in 2023, Kenya-based TCM researcher Wei Ye noted: “The development puts the world’s donkey population at risk and disrupts the livelihoods of those involved, especially in areas with large populations of the animal, such as East Africa, Central Asia, and South America.”

Ye’s essay relates a story about meeting a Chinese businesswoman named Tong in Nairobi as she sought to buy donkey skins to make ejiao. Tong bought them from a Chinese businessman who had been buying them from Kenyan villagers and stockpiling them. The demand for ejiao has grown rapidly in recent years as Chinese TCM users seek “life-nurturing” practices, Ye wrote.

According to The Donkey Sanctuary, a U.K.-based animal welfare group, China’s ejiao production grew from 3,200 metric tons in 2013 to 5,600 metric tons by 2016. Production is expected to triple by 2027.

The TCM market needs nearly 6 million donkey skins each year to meet demand, according to researchers at Warwick University in the U.K. That demand could reach nearly 7 million by 2027.

Kenya banned the slaughter of donkeys for their skins and meat in 2020. The country’s high court overturned that ban in 2021 after slaughterhouse owners fought it.

Botswana, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Tanzania and Uganda also have banned the practice. In 2024, the African Union passed a continentwide ban on donkey slaughter for 15 years.

Yet, the slaughter continues across the continent. The year that its ban was overturned, Kenya exported 160,000 donkey skins, according to Brooke researchers.

In African countries that have banned donkey exports to China, there often are no penalties for violating the ban, so illegal trade continues, according to Brooke researchers.

Nigeria has become a hub for legal and illegal trafficking in donkey skins to China. Egypt is home to a black market in donkey skins bound for China, according to researchers. The border between Burkina Faso and Ghana remains a hot spot for the trade.

Kenyan authorities recently broke up an illegal donkey slaughtering operation in the town of Kithyoko near the border of Machakos and Kitui counties. Donkeys were transported to the community from across the region to be slaughtered.

Ultimately, the TCM trade in donkey skins harms rural Africans as much as it harms the animals they rely on for transporting goods, plowing fields and the like, according to Brooke.

“The scale and rapid global spread of the donkey skin trade to fuel China’s demands for ejiao is unsustainable,” Brooke researchers wrote. “The trade is having devastating consequences for donkeys and their owners around the world, which are felt most keenly by vulnerable people in poor communities.”